The politics of industrial strategy

Do the Blairites really think they can win a Labour leadership contest on the back of Thatcherite economics?

Michael Lind is an American political theorist who bridges the divide between academia and the think tank world. According to a book review published in The New York Times in 1995, he “defies the usual political categories of left and right, liberal and conservative”. That undefinability probably is how he came to give a talk earlier this month at Policy Exchange as David Cameron’s favourite think tank tries to broaden its appeal.

The talk was billed as a discussion of how the left could move past populism. This was an odd way for Policy Exchange to frame it because it treats the issue as a blank slate whereas it seems clear that Starmer is already very much in that game. Nonetheless, the talk itself was useful in that it injected some urgently needed realism and political context into the debate on industrial strategy.

The talk was divided into two parts, the problem and the solution. The analysis of the problem dealt with the US and the UK at the same time and in this way managed to helpfully boil things down to essentials. Looking forward, it articulated quite naturally things that are at one and the same time both obvious and unsayable in the UK.

The Problem

In Lind’s view, we’ve gone through shifts in policy paradigms. A mid-century settlement gave way to the neo-liberalism of Reagan and Thatcher, which was carried on by Clinton and Blair. This, too, is now over. Trump and Biden both broke with it decisively, in Biden’s case via industrial policy, foreign policy and a newly pro-labour approach.

The economic aspects of neoliberalism provoked a populist reaction, particularly from working class former constituents of centre-left parties, for two promises were broken. The growth promise was that industrial countries would shed low-wage, less-productive jobs to countries like China and secure the industries of the future – not just services but advanced manufacturing too. These knowledge intensive industries would create better jobs than the ones that were being lost. The sharing promise involved a redistribution for the losers, so factory workers who were laid off would be retrained or even paid compensation

Lind says, “Needless to say, this did not happen. Neither the neoliberal growth model nor the neoliberal sharing-the-gains model from growth ever came into being. It never really existed. What you got instead of this knowledge economy was economies on both sides of the Atlantic driven by asset price inflation and by immigration-driven population growth. … We got the deregulation, we never got the redistribution because in a globalised economy it's very easy to hide your corporate or individual wealth in the Cayman Islands.”

The asset bubbles included both shares and property, which priced many people out of the cities they wanted to live in. Meanwhile, identity politics alienated many of the centre-left’s original electoral base.

(Lind also says the effect of the immigration was also to suppress wages, on which I’ve seen arguments that this was not the case in the UK, so my jury is out on that one.)

Lind’s analysis is strikingly similar in its fundamentals to that this week offered at the global level by Paul Mason, the social democrat and former economics editor on Newsnight. Indeed, Mason has an even starker way of summing up the predicament we are in. Since the mid-2000s when growth ground to a halt, we have been in a zero-sum game that plays out at many levels: a factory can be built here or in China; a job can go to a man or a woman. Workers are sensitive to this but social democrats, such as the Labour Party, aren’t.

I concur with Lind and Mason. In the UK, the neoliberalism starts with Thatcher and is continued by Blair and Cameron, what I have called Thatcherism Mark II. During this period there are two waves of de-industrialisation, first under Thatcher and then under New Labour. These depress the green regions on the map below even as the asset bubbles and fragments of the knowledge economy boost the red regions. This is how we end up with a country divided in two, with a huge left behind area whose poverty compared to the other part is starker than that between East and West Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

How deep is the blindness of the social democrats? At the last Labour Conference, the political scientists David Klemperer and Colm Murphy identified three Labour tribes. The neo-Bevinites and neo-Blairites are preoccupied by achieving growth and the neo-Croslandites preoccupied by sharing the spoils of growth. None of them is facing up to the reality of a present in which there is no growth.

Now for the unsayable stuff.

The Solution

For Lind, the way forward is with different growth and sharing models. The growth model should aim at increasing productivity. So far, so conventional. But Lind went on to make a pointed observation, citing Ralph Gomery, formerly the chief mathematician at IBM. Is it better to invent the automobile or make it? Answer: it is better to make it. That’s where the money is, that’s where the jobs are.

“If you invent a new technology and you immediately then license it for production in another country, well who in your country benefits from this invention? The great entrepreneur, the inventor gets this stream of licensing royalties from abroad buys a country house, a yacht, fleets of servants, but other than that your economy doesn't improve much. If you have massive high-tech manufacturing centres and the accompanying high-tech logistics and you're cranking out, let’s say electric vehicles or drones for civilian use, to hundreds of millions of consumers then you've got your manufacturing base, this permanent asset.”

One aspect of this that Lind doesn’t go into is a difference between a PLC selling a firm it owns and founders selling up. If the PLC sells, the receipts will generally be reinvested in some kind of commercial activity. If it is founders, then the receipts can all go on consumption. That’s what happened when I sold the company I founded.

Lind says the sharing model should be based on restoring worker bargaining power. The UK should consider returning to the trade boards (later wages councils, that ran from 1909 to 1993 and set industry-specific minimum wages). In the current French system, only about 10 per cent of workers are unionized but nevertheless all workers are covered by the collective bargaining agreements they strike.

Lind’s ideas as to how to both grow the economy and share the fruits are pretty much unsayable in the UK and this was reflected in the meeting by the complete absence in the Q&A of any discussion of this portion of his talk. Let’s start with the sharing. It is evident that Keir Starmer’s government is moving rapidly to provide workers with a wide range of improved protections, but what is within the current Overton window of possibility in polite discussion falls far, far short of adopting the tripartite French model that systematically brings together workers, employers and government.

The idea of re-introducing trade boards feels like a breath of fresh air. As far as I can establish, the last time anyone seriously proposed this was the TUC in 2013, when it, like Lind today, was explicitly aiming at increasing the share of national income taken by workers. Interestingly, the TUC pamphlet suggests linking the new trade boards with industry panels at the time being developed by the government to support economic growth, a kind of body that could emerge at the sub-sectoral level from the forthcoming industrial strategy.

Whatever the economic effect, trade boards would undoubtedly have a beneficial political effect. Part of the story of the last 50 years, left out by Lind but important on many other accounts to the rise of populism, is the withering away of the institutions that used to mediate politics, including both political parties and trade unions. Rebuilding such mediating institutions is one of the recommendations for moving past populism made by the theorists Chris Bickerton and Carlo Invernizzi Accetti, and hence fits naturally into Starmer’s programme. Restoring the trade boards could be a significant step in this project, providing a mechanism for dealing with the central issue of salaries and opening up lines of representation and liaison on a host of other issues.

On growth, Lind is very diplomatically delivering the same message that other American friends do. The UK’s research and innovation effort has become detached from its industrial effort and consequently is failing the country in a quite fundamental way. It’s easy for Americans to see this because over there it is working in a different and much more effective way.

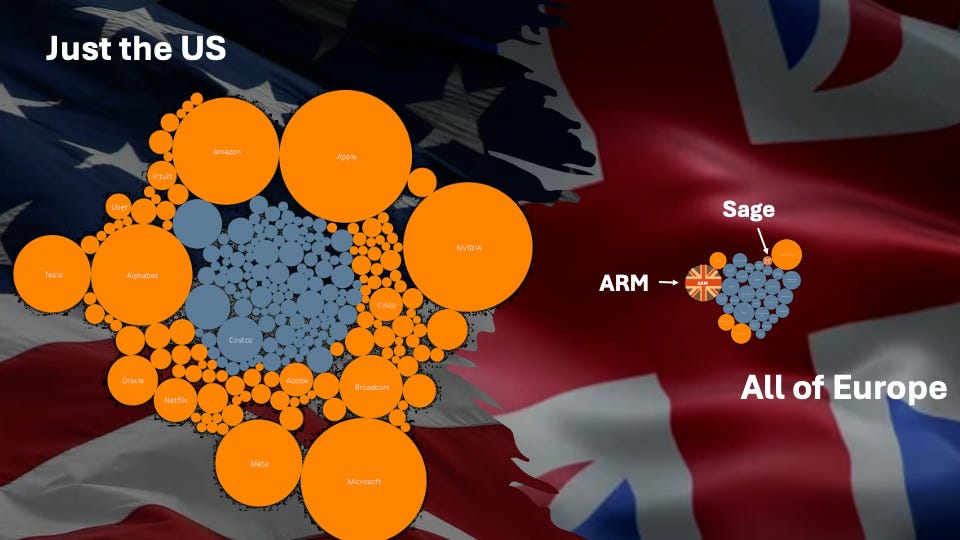

Here’s a comparison between companies formed from scratch in the past 50 years in the US and Europe, including the UK, that are now worth more than $10 billion.

The key reason for the disparity between the US and the UK is not the start-ups. Per 1000 of the population we keep pace with the US on that. The problem lies in the later stages of development when UK firms commonly are either sold to an American firm in a trade sale or move to the US in order to access the larger pools of capital there. That is, we lose our firms as the idea turns into a product. We are failing Lind’s Ralph Gomery test.

I wish there was a solid body of economic research that I could point to that answered the key questions concerning the linkage, or otherwise, between the UK’s innovation system and its wider economy, but it barely exists. Under Thatcherism Marks I and II, there was no need for it. One obvious point is that we need to distinguish, as Lind does, between the ownership of the company being foreign and its substantive activity being foreign. The two do not always go hand in hand. ARM, the huge chip design enterprise in Cambridge, is owned by Japan’s Softbank and is doing great for the UK. However, they often do. Take the story of Kymab.

In 2009, Kymab was the first company spun out of the Sanger Institute in Cambridge, then best known as the UK’s arm of the Human Genome Project. It grew until it occupied the lab below on the Babraham Research Campus, five miles south of Cambridge. Amongst other things, it developed a targeted monoclonal antibody, KY1005, that showed great promise as a treatment for severe eczema. It had the potential to become a world-leading biotech company based in the UK. But then, in 2021, it was bought by the French pharma giant Sanofi for $1.5 billion. Today the lab is empty. There is nothing left in the UK except, as Lind says, maybe a few country houses, yachts and servants for those Cambridge people who had shares in the company.

This is not what happens in the US. In the US, if a viable firm gets bought, it is usually by another US firm. The American research and innovation system primarily supports the substantive American economy. By contrast, you can make a perfectly respectable argument for the proposition that the British research and innovation system also primarily supports the American economy. That, as Lind is reminding us, is where the ideas end up. That is where the products and services are put into production. That is where the big money is. That is where the jobs are.

The innovation ecosystem we currently have in the UK is failing the nation. It isn’t levelling up the green regions on the map. Quite the reverse. Its benefits are limited mainly to a small number of people in the red regions. And the primary reason for this is not that our research base is weak or that we have too few startups or that they have poor management or any one of hundreds of other real issues that require attention. Nor even is it that the knowledge economy, to the extent that we’ve got one, is centred on the Golden Triangle: ask yourself, where are you going to build a new factory – in expensive, middle-class Cambridge or in cheap, working-class Sunderland? It is simply because we do not hold on to firms as the idea matures into a viable product. It is because, in their neoliberal enthusiasm for a globalised world, Thatcherism Marks I and II fundamentally stopped caring whether things were made in the UK or not.

Politics

It is uncontroversial to say that a central goal for the coming industrial strategy should be to make more stuff in the UK. However, push comes to shove when you ask what if anything is going to be done in pursuit of that aim. The burden of the above analysis is that a key goal should be for the UK to retain the fast-growing firms that emerge out of our innovation ecosystem, to retain for British workers the benefits of the dynamism the green paper wants to nourish. This is one overarching objective that could and should distinguish Starmer’s vision for the economy from past failure. (It is, by the way, a demand that Angela Rayner’s Department for Housing, Communities and Local Government could quite reasonably make of the industrial strategy.) A first stop in devising a suitable approach could then be Competing in Advanced Manufacturing: The Need for Improved Growth Models and Policies by Gregory Tassey, an economist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in the US.

The road in this direction is however blocked by the very people whose failure we are dealing with, the remnants of Thatcherism Mark II, who have reinvented themselves as the techno-zealots of Thatcherism 3.0.

The Labour part of Thatcherism 3.0 consists of Blair, Blairites generally, the Tony Blair Institute, and individual politicians associated with it. Blair has never conceded that New Labour’s economic approach was flawed and, so far as I know, no report from the TBI has ever acknowledged the central role, as described by Lind, that this has played in the UK’s problems. If, like John Major, you retire after Number 10 to watching cricket, it perhaps hardly matters whether you acknowledge your mistakes. But if, like Blair, you still want to play a real and pivotal part in politics, then this kind of refusal creates a fundamental problem. You can’t deal with the substantive problem facing the country. And this is exactly what we see in the output of the TBI which, despite more than 70 techno-oriented reports in the past two years has never stepped outside the neoliberal confines established by Thatcher when she ruled out government support for near-market research – that is, support for the kind of activity that turns ideas into products.

The Conservative part of Thatcherism 3.0 consists of straightforwardly neoliberal politicians that pre-date the turn to populism embodied by the likes of Johnson, Truss and David Frost. These include particularly William Hague, the joint author with Blair of A New National Purpose, the foundation stone of the TBI’s techno-zealotry, David Willetts, Cameron’s Cabinet-level science minister, and Greg Clarke, Theresa May’s Cabinet minister for industrial strategy.

The Conservative and Labour parts came together to establish the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology in the first place, the TBI calling for the creation of such a department in the same month that Rishi Sunak created it. This entrenched the exact problem Lind is bringing up by creating a department focussed on inventing things rather than making them. Today, their calling card is the idea of a ‘cross-party consensus on science’.

Having birthed DSIT, Thatcherism 3.0 does not need to change its direction with the change of government. It has already imprinted its mindset on a departmental bureaucracy that has never shown any commitment to retaining fast-growing firms in the UK. Instead, it seeks quiet, gentle evolution. And this in fact is the direction of travel under Peter Kyle, the DSIT Secretary of State.

It can be seen in Kyle’s pre-election promise to pharma companies to maintain the R&D tax breaks regime, a promise that will cost taxpayers about £10 billion a year. It can be seen in the absence of new thinking on the role of innovation in the green paper on industrial strategy and the absence of any commitment there to substantive change aside from the Net Zero agenda. It can be seen in the appointment to the new Industrial Strategy Council of Greg Clarke (the tip of an iceberg since the visitor’s book at DSIT remains full of Conservative Party courtiers). It can be seen in the regulation of AI, where Kyle quietly dropped the news that his main move would be to give legislative force to the Conservatives’ voluntary safety regime at a select committee hearing earlier this month.

It is a grim outlook, but one thing that might save us is political ambition. Recognition of the importance of the factional dynamics I have been describing in recent essays is seeping out into the mainstream. At the Financial Times, Stephen Bush was kind enough to refer readers to my article on Starmerism as a starting point. At the New Stateman, George Eaton has taken the idea forward by combining it with the question of who might come after Starmer as leader:

As the government seeks to define itself, such factional differences have taken on a heightened significance. For the soft left, state intervention and a social-democratic economic agenda are crucial to Labour’s success (“we want GB Energy to show that public ownership can work,” Miliband said when I interviewed him in September). Blairites, by contrast, put greater emphasis on public service reform and positive relations with business.

Starmer’s administration combines elements of both worldviews. He has embraced public ownership, stronger workers’ rights and tax and spend (and empowered Miliband, a friend and near-neighbour). But he has also put Blairites past and present at the heart of his administration and eschewed fights with business – wooing firms such as DP World and BlackRock.

For some, this is evidence that Starmer, like his hero Harold Wilson, can preside over competing tendencies. For others, it is proof of a government that lacks ideological definition.

That’s one reason – along with Starmer’s early unpopularity – why discussion in Labour circles has already turned to the next leadership contest. Back in October, I wrote that MPs envisaged a future in which Streeting and the soft left Angela Rayner faced off against each other (a scenario the latter has since publicly joked about).

Streeting’s allies reject accusations that he is “on manoeuvres” (noting that his recent interventions would hardly endear him to the Labour membership). But at a time of government strife, the health secretary has made clear he is his own man.

Reading between the lines, it seems Camp Streeting is alarmed by the idea that he might get labelled a Blairite – hence the flourish at the end about him being his own man, a claim which in both ideological and economic terms so far has rather little evidence to support it. The alarm is entirely logical for it is blazingly obvious that no one who is clearly understood by the party membership to be either a Blairite or a neoliberal can possibly be elected leader.

Streeting, like Kyle and most of the other Cabinet ministers involved, is young and new to the job. None of them have to end up labelled Blairite or as participants in the latest iteration of Thatcherism. Rather, they will define themselves by their choices. I just hope a cool view of their own prospects will lead them to realise that techno-babble won’t save them if they persist with the neoliberal, Thatcherite economic policies that got us into this mess.

Thanks, but if the UK would be part of the EU some issues might be less problematic

Do you think high tech manufacturing would generate many jobs, due to its automation, in any case?