Trump, Starmer and the populist tide

Old concepts such as left vs right, trust and class aren't enough to explain the trouble we're in

Donald Trump’s election to a second term inspires dread twice over. First, because of what he may do – we fear for NATO, trade, the climate and the Federal Reserve (guarantor of the UK’s outsized financial system). Second, because of what he is – part of a tide of threatening politicians across the West that seems to retreat only to advance again. It is the second dread that is most perplexing. We can see that politics is changing, but how and why? Often the forces shaping these changes seem mysterious.

This sense of mystery is not limited to the curious public but extends to political scientists. There is no general agreement on how to understand the world we are now in. Part of the problem is language: is Trump populist, authoritarian, far-right, a Latin American-style strongman or, as Kamala Harris said at the end, a fascist? But this is merely a symptom of a deeper problem, that the old concepts we had no longer seem to explain much. As a sardonic Cas Mudde, one of Britain’s leading students of the far-right, put it after Trump’s victory: “I’m happy to see that, as I understand less and less about far-right politics, there are more and more people in the (social) media who seem to be all-knowing experts on the topic.”

A concrete way into the mystery is to look at the question of trust, a major concern for both Labour and the Conservatives. It lends itself to a simple question in attitudinal polling and hence to a frequent supply of data. Looking back over the results of the last election, Christabel Cooper, the director of research at the think tank closest to Keir Starmer, Labour Together, has written:

According to the most recent British Social Attitudes data, the percentage of Britons who trust politicians has more than halved since 1986. This distrust is not just seen in numbers on a chart. It translated into actual voting behaviour in the form of the second lowest turnout for an election since and the lowest combined vote share for the two main parties in the post-war period.

In the eyes of Cooper, a central problem for Labour is that “… specific antipathy to the Tories has evolved into much higher levels of distrust of the political system”. However, this short-term framing of the issue is at odds with her own observation of a long-term decline going back at least 40 years.

Cooper’s data on trust is drawn from responses to a question on whether politicians can be trusted to put country before party. In an age of populists and kleptocrats, it’s a far from perfect question, but the general picture tallies with responses to other questions. Trust on this measure fell sharply between 1986 and 1996, from 40 to 22 per cent. It recovered to 33 per cent for a year with Labour’s victory in 1997 but then plunged again, hitting 16 per cent in 2000. It recovered to an average slightly above 30 per cent for a while but then fell back to 16 per cent in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. In the year Gordon Brown went to the polls, 2010, it was 20 per cent and it has hovered around there since, dropping to 14 per cent in 2023.

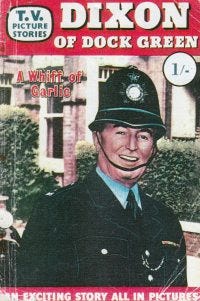

Restoring the trust lost under the Conservatives will get Labour back to a puny 20 per cent. To get higher, Starmer is going to have to get back to levels not sustained since before 2008, and even Blair only averaged 25 per cent. Looking further back, it seems obvious that today’s society is at some fundamental level less trusting in the state than the one in which Dixon of Dock Green was a cozily plausible account of the role of the police. Something deeper is going on and needs to be grasped if the Trumpish tide is to be held at bay.

Among the various attempts to make sense of it all, the most useful I have found is the idea of technopopulism as advanced by the academics David Bickerton and Carlo Invernizzi Accetti. Through this lens, the depth of the problem Starmer faces in winning trust for his government becomes clearer, as does the strategy he is pursuing. However, since we are discussing new concepts, the next bit is quite abstract. Strap in.

Technopopulism: The New Logic of Democratic Politics argues that the familiar logic of left-right politics in Western democracies has been overlaid and largely displaced by a technopopulist logic. In this, ideology is relegated and technocracy and populism are promoted. These two are not, as is often thought, opposed; rather, electoral success comes to those who find effective ways to fuse them. The book draws its evidence from Europe and so exponents (as at 2021) include M5S in Italy, Emmanuel Macron in France, Podemos in Spain and New Labour and Boris Johnson in the UK. In a subsequent podcast, Accetti has suggested the list also include Trump.

This shift is primarily ascribed to two factors, one structural, one ideological. Structurally, there has been an alteration in society such that the large blocks of population whose interests were represented by left and right – e.g. the working class or Catholics – have dissolved. In addition, the mediating capacity of institutions such as trade unions or political parties has declined. Ideologically, there has been an alteration in the nature of political debate such that fundamental conflict between left and right has been replaced by agreement on ends. The effect of these developments has been to separate society from politics, felt as an unsatisfying ‘lightness’ in politics that has fed distrust in politicians and paved the way for a new kind of political logic.

“In the absence of any effective mechanisms of mediation between them, the relationship between the social and the political took the form of a mass of disaggregated social interests and values, on the one hand, and unitary conceptions of the ‘popular will’ or ‘common good’ on the other.”

This background analysis, which involves synthesising the work of many other political scientists, I find helpful to start with. For example, listening to Steve Richards talking interestingly about “the left behind”, you get the idea of a particular problem. Here that problem fits into a bigger picture, you see the left behind as people economically and politically marooned by the agreement on ends.

Going on, Bickerton and Accetti understand both the technocracy and populism parts of technopopulism as modes of political action. Each mode has “ideational” and “organisational” aspects; it’s a 2x2 matrix.

Technocracy is defined as:

ideational – a claim to a particular kind of competence or expertise that presumptively entitles its possessor to legitimately rule over others

organisational – a direct relationship of trust between the possessor of this competence and those he or she is supposed to rule over.

Populism is defined as:

ideational – presenting the country as divided between a pure people and a corrupt elite

organisational – the claim of the leader to exclusively represent the people, free from any reliance on the now vanished connective tissue of people and institutions that previously linked blocks of voters to ministers.

We can say that Trump or Tony Blair are technopopulists and use technopopulism to cultivate trust that is otherwise hard to come by, but this a kind of shorthand. What Bicketron and Accetti really have in mind is that politics itself has become technopopulist and that some have been faster to embrace this new reality than others. It’s like the tide, you can swim with it or against it, but the going is easier if you swim with it.

Bickerton and Accetti devote a section of the book to making the case that New Labour was technopopulist. Alternatively, instead consider briefly a descendant of New Labour, the cross-party project of Thatcherism 3.0 described in my last article. In this project, New Labour figures such as Blair and Ed Balls, Gordon Brown’s right-hand man, combine with small state Conservatives such as William Hague and David Willetts, promising to use science and technology to transform the state.

On the technocracy side:

ideational – the movement’s special competence lies in mastery of the forces claimed to be shaping our world, science and technology

organisational – the direct 1-Everyone bond of trust is missing for the simple reason that there is today no candidate for Prime Minister; Thatcherism 3.0 is not campaigning for election at this time but merely preparing the ground.

On the populism side:

ideational – the idea of a corrupt elite comes up in phrases such as “status-quo forces” in the project’s founding document, A New National Purpose

organisational – the claim to exclusively represent the people comes up in the idea that Thatcherism 3.0 represents a supreme consensus and, as Ed Balls put it to George Osborne on their podcast, “it is only through the consensus that the nation moves forward”.

With the technopopulist framework in mind, let’s look at Keir Starmer as he expressed himself through his victory speech in Downing Street on 5 July.

On the 2x2 matrix, Starmer scores a big fat zero. On the populism side, he does not conjure up a corrupt elite to villefy, nor claim to exclusively represent the people. In terms of technocracy, he claims no special competence nor does he try to establish a 1-everyone bond of trust. Instead, he makes it all very collegial:

… whether you voted Labour or not…

In fact - especially if you did not…

I say to you, directly…

My government will serve you.

Politics can be a force for good - we will show that.

In the framework of Bickerton and Accetti, Starmer is the exact opposite of Blair, as he both was and is today. This has to be emphasised because he is recruiting increasing numbers of Blair staffers to his team and is proving to be as centralising as Blair. He is building a substantial policy unit at Number 10 and maintains tight control over both the development of policy within the party and the messages the Cabinet put out.

This analysis puts the accusation that Starmer is boring into context. Compared to a technopopulist, he is boring. It’s not all about him, him, him and his charisma. But this is less a character trait, more a deliberate choice to eschew (techno)-populist tropes. This is, I think, one of the reasons underlying the lack of narrative that has been widely noted. The me, me, me of the populist provides a ready narrative for everything; through them, politics becomes emotionally meaningful even if this meaning is detached from the material reality; looking inside myself, I find that Blair and Johnson are more vivid in the memory than Brown and Theresa May. For anyone who rejects that path, it’s harder.

Rather than personally boring, it seems to me that Starmer is politically interesting in that he is trying to do something new. The twist is that he’s doing it in a way that seems on the surface to be old fashioned.

Labour is once again comfortable talking about class, which is itself a throwback to what came before technopopulism. Extending VAT to private schools can be cast as straightforward class politics. Restoring the NHS to its former glory is similarly emblematic of past Labour heroics. And any move, such as the strengthening of workers’ rights, that rolls back the Thatcherite consensus that runs through New Labour and Cameron’s governments, inevitably is a kind of reversal. The Budget as a whole was presented as one that was on the side of “working people”, a frequently used term that is easily read as a synonym for the working class; again, very 1950s.

Even the approach to communications is a throwback, reminiscent of traditional Unilever branding. Brand values (e.g. competence, duty, on the side of working people) are consistently evoked; products (missions) are developed and promoted to the target segments via broad-brush messaging delivered in broadcast fashion. But why these particular products are being offered to us is, as with any corporation, as opaque as the one-way mirror used with the focus groups. If a product loses traction, as with the growth mission, or becomes too expensive, as with the green mission, it is reformulated and repackaged. There is no narrative, no use for social media other than as a vector for dull public service announcements, just an ear for tone so that when, as now, times are tough, the messaging is dour.

After the (techno)-populist chaos of recent years, there is something attractive about going back to past solidity. But technopopulism itself is a response to the failure of that old politics, emerging from the decay of the blocks in society, the mediating institutions and of idealism itself. How does Starmer avoid simply being crushed in the same way that Trump crushed Kamala Harris and Blair crushed John Major?

An answer emerges from the gap between the apparent old-fashionedness of the Labour strategy and the reality. The monolithic working class of the 1950s no longer exists, Labour’s 2024 electoral coalition is not remotely monolithic and the party itself no longer attempts to mediate between class and government. “Working people” includes most of the middle class alongside the working class. Reflecting all this, in his first speech as Prime Minister Starmer limited his references to the working class to one in which he referred to his own upbringing 50 years ago. Thus the strategy is not truly old fashioned. It is not truly class politics. Rather, it is an easily misunderstood echo of it.

In this, Starmer’s hair is very much on brand. The cut is a short back and sides that he could have watched his dad take to the factory. The almost-quiff also has a slightly Brylcreamed quality that again seems a throwback. However, that twist of hair is not greasy, has good body and always has terrific definition. It is sculpted in a very modern way, one that is allowed for only by modern styling products. He is drawing on an aesthetic of the past to create something new. As in the photo, it is genuinely at home on a football terrace, one of many locations that can no longer be simply labelled working class.

At the end of their book, Bickerton and Accetti argue:

“…to fight back populism and technocracy together it is necessary to revive a conception of politics as competition between conflicting social ‘parts’, which stands for the pursuit of substantively different political goals.”

If you consider “working people” a social part, Starmer’s approach fits this pattern. His goal surely is to substantively shift the balance of the economy so that it favours working people. And the use of the term is a logical reaction to the complexity of today’s social reality (as explored in Laura Hood’s podcasts). There are working class people, people doing manual labour and whose parents did the same, plumbers for example, who are financially secure. At the same time, there are middle class people working in pubs and flat-sharing into their 30s.

Nonetheless, I struggle to see “working people” as a social part. It’s too diffuse and has too many competing tensions within it – for example, most parents sending their children to private schools are working. Rather, I think “working people” has to be understood as a term that Labour’s electoral coalition, as it is and as it may become in future, can identify with. It is less an actually existing part of society and more an idea that is being created, one that in a blurry sort of way does correspond to the substantive political policies Starmer is pursuing.

So, in this blurry, ideational sort of way, I think we can see Starmer as pursuing a new strategy for pushing back against the Trumpish tide, one that seeks to regain trust by reinterpreting rather than implementing the kind of approach urged by Bickerton and Accetti. Let’s hope it works.

Another fascinating piece. I see the five missions have now been further redefined and reduced to “bills and borders”. I still think Starmer is closest to Wilson with his emphasis on technological/administrative solutions without the latter’s ability to connect with TV audiences (he recruited Tony Benn to help him with this). I know that “winning the argument” carries certain connotations in the modern Labour Party but (as per Steve Richards) you’re hardly going to connect with voters if you never seem keen on engaging with them. Doesn’t help when several of your policies are more likely to raise prices than lower them.

"Working"? He wants so much to say "normal"... and I don't blame him.

We have entertainment politicians... getting points for saying extraordinary things.

No one - well apart from spivs and genocidal chancers - is served by populism... it is a hit.. nothing more... and we all have to pay for it in the morning.