Into the kill zone

A more assertive America gives Big Tech a darker shade

Silicon Valley is proving true to its roots in dealing with the new Labour government in the UK. It is moving fast and breaking things.

Within days of the election in July, Peter Kyle had announced a new cross-departmental drive for tech adoption from within his Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. By September, his Cabinet colleague Wes Streeting was promising the same in the NHS.

The new Parliament returned from the conference recess on 7 October and got down to work properly for the first time. Five days later, Johnny Reynolds, the Secretary of State for Business and Trade, made the head of Microsoft UK the chair of the new Industrial Strategy Advisory Council.

On 3 December, Kyle told MPs that the new government’s approach to regulating AI would be as hands-off as the old one’s. Regulation would be limited to giving statutory force to the voluntary, safety-based regime that has already been embraced by Big Tech.

On 17 December, Kyle announced his preference for a regulatory regime in which creators would have to opt-out to avoid giving Big Tech freedom to train their AI on copyrighted works.

On 11 January, Kyle promised “…a very high threshold…” for the kind of social media content that is to be considered harmful under the Online Safety Act.

On 22 January, Marcus Bokkerink, the head of the Competition and Markets Authority was ousted by Reynolds. His place was taken by a former head of Amazon UK.

Six days later, the CMA announced that the result of a three-year investigation into the monopoly of Big Tech cloud services was to be… another investigation.

For Big Tech, that is win after win after win. Ministers are now pushing every public sector body in the land to buy their products. Their own people can now scrutinise and shape the policies that most immediately impact on their British prospects. The twin treasure troves of British creative works and NHS data are being opened up to them. The only existing lever that might be used to curtail the editorial power of X and Meta to determine who sees what on social media is not going to be pulled. They will remain free to monopolise cloud services and extract ever higher rents. They will be free to do as they please with AI.

This direction of travel is not new. The previous government also tended to yield to Big Tech and, while Kyle’s department was created under Rishi Sunak, it had support from his allies in the Tony Blair Institute. Conservative support is how, for example, Palantir acquired a central position in NHS data – a decision that even former Conservative Cabinet ministers now acknowledge was a mistake. Nonetheless, Big Tech has moved faster in the last six months than it has previously. And it has broken something, which is the UK’s longstanding commitment to the principle that competition is good, both for consumers and for growth.

The kill zone

On ousting Bokkerink, Reynolds issued a statement saying, “We want to see regulators including the CMA supercharging the economy with pro-business decisions that will drive prosperity and growth, putting more money in people’s pockets.” This apparently innocuous form of words is deeply misleading.

There is a genuine sense in which regulation inhibits growth. For example, environmental regulation inhibits the building of infrastructure, which supports growth. HS2 and the proposed third runway at Heathrow airport are cases in point. Rachel Reeves’s decision to press ahead with the third runway is concrete evidence of Labour’s determination to curtail the impact of such regulation. It is a decision that i) is “pro-business” in that it is welcomed by business; ii) “supercharges the economy” in that it will generate growth; and iii) will thereby put money in pockets.

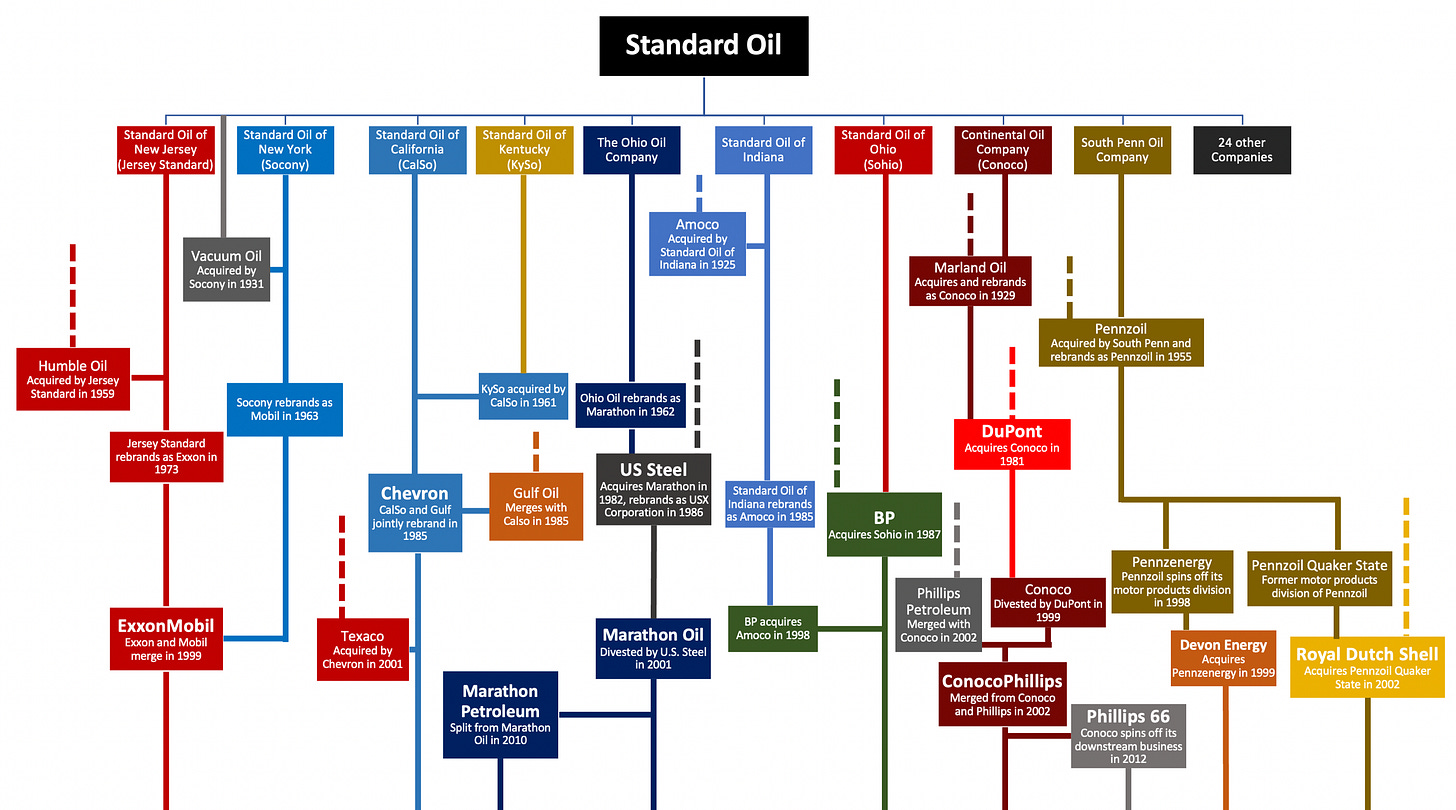

However, the CMA’s prime concern, regulating monopolies, is a different matter. Without regulation, monopolies just get fatter and badder. Instead of creative destruction in the economy, there is rent-seeking with consumers paying the price. Instead of choice, there is take it or leave it. Instead of growth, there is stagnation. Businesses, at least the big incumbents we tend to hear from, hate this kind of regulation, which came to prominence a century ago when it was used to break up Standard Oil in the US. Big Tech firms fear it could be used to break them up in the same way. Thus, in the sense in which Reynold uses the term “pro-business”, this kind of regulation could be called “anti-business”. However, there’s mountains of economic evidence that competition is not only good for consumers but also promotes competitiveness and growth. So it is the presence rather than the absence of this kind of regulation that “supercharges the economy” and puts money in pockets.

In 2020, Joachim Klement, an investment strategist based in London, gave a good example of how the monopolistic dynamic works in tech:

“A new study from the University of Chicago has documented how Google and Facebook defend their dominant market position by simply buying up any serious competitor and thus stifling investments in social media and internet search companies.

There is a suspicious decline in VC investments in social media startups for the last four years or so. This decline is mostly fuelled by the fact that VC investors see no opportunity to compete with the might of Google or Facebook. This becomes particularly clear when one looks at the VC investments that flow into software startups. If Google or Facebook recently acquired a competitor, that field experiences a significant decline in investments while other areas see additional investments.

Venture capitalists call these areas where Google, Facebook, and other major companies suck up every competitor before it can become a threat the “kill zone”. And these kill zones reduce competition and ensure that Google and Facebook can continue to dominate their respective markets.”

An acute example of what is at stake in the UK concerns healthtech. There is a steady stream emerging of start-ups exploiting AI to offer novel applications to hospitals. For the UK, it has the makings a virtuous circle. The firms emerge from the NHS, find their market in the NHS and then expand to sell overseas. In prospect is a repeat of the dynamic that gave the UK a clutch of leading pharmaceutical companies. Indeed, this prospect has been championed by Streeting. However, all this is likely to be destroyed if Big Tech – especially Microsoft, which has wide-ranging contracts with many hospitals – are permitted to bundle AI with their cloud services. The AI applications coming out of Silicon Valley may be worse than those offered by the British start-ups, but they will be free, at least to start with. That British ecosystem of AI healthtech will never get started. It will be sucked into the kill zone.

I have direct experience of this sort of thing. It was when Elsevier began to bundle for free products that my comparatively small company sold that I stopped trying to conquer the world and went looking for a buyer. I found one in a big American technology company.

The natural solution to this problem is a CMA that says to the Big Tech monopolies, “No bundling – especially of AI”. This is the kind of regulation that Big Tech calls ‘over-enforcement’ and, in the eyes of Silicon Valley, its days are now numbered. “The UK government is sending a clear signal, less over-enforcement please,” Politico was told by the Chamber of Progress, a lobby group whose backers include Amazon, Meta, Apple and Google after Bokkerink was ousted.

To sum up, digital services such as cloud storage are the roads and railways of the 21st Century. Consumers and businesses rely on them, as does the public sector and the government itself. These services are dominated by Big Tech, which thereby controls what can and cannot run across them. Big Tech maintains its monopolistic ecosystems in part by establishing a kill zone around them. The monopolies extract ever-higher rents while depressing growth and preventing the development of indigenous UK firms in the fastest growing segment of the global economy, now including AI. They are thus inimical to i) the dynamism at the heart of the green paper on industrial strategy, which foresees new high-productivity, high-growth firms displacing established low-productivity, low-growth firms; and ii) the long-run economic logic of raising revenue by raising Employer National Insurance Contributions, a move that squeezes firms in low-productivity sectors such as hospitality and makes sense only if we get more firms and jobs in sectors such as tech. They also bring with them American attitudes to privacy and workers’ rights that are light years away from those of most Brits.

The willingness of a government that has staked its political destiny on growth to agree to a measure, installing the Amazon guy at the CMA, that it knows undermines growth casts a shadow over all the other pro-Big Tech decisions taken recently. If Big Tech is to be so favoured, then it is not necessary for the government to sincerely believe, for example, that an opt-out policy on copyrighted works actually is good for Britain in order to advocate it.

Equally, the limitation placed on the future of the British economy is so fundamental that it makes a mockery of other pro-growth measures the government has announced. A new runway at Heathrow or the restoration of the railway line between Oxford and Cambridge pale into insignificance when set against an attitude that seems to allow Big Tech the freedom to shift any British firm it chooses into the kill zone, a stance that consigns us to an industrial future revolving around hairdressing and scones.

Andy Prendergast, national secretary of the GMB union, has said the Amazon guy’s appointment to the CMA, a body intended to combat unfair market monopolies, “is a slap in the face to workers”. A diverse collection of voices – including Vince Cable (the Liberal Democrat Secretary of State for Business 2010-2015), British tech firms, publishers and Which? – has also written to Reynolds complaining. These noises are just the start. Pretty much every competition economist in the country is lining up to tell the government that, if you want growth, let the CMA, do its job, especially its new Digital Markets Unit.

Hence the overriding question is, why? Why is the government putting Big Tech before growth? The idea that the recent decisions are balanced by promises of a few server farms or research labs makes no sense – in the long run, these sorts of commitments are orders of magnitude less significant.

At one level, we can all glimpse an answer to this question: it is simply that the Americans are powerful. But how is that power to be understood? How is it making its presence felt in the here and now? And what else might be the ramifications of it? If, like me, you’re trying to understand the ramifications of Donald Trump and Elon Musk but have grown up on Anglo-American buddy shows like James Bond and Mission: Impossible, it’s hard to know.

The continental power

The way Helen Thompson tells it, the story starts about 1850.

The British Empire is at its peak but the United States is emerging from its Civil War and, behind tariff barriers, begins to industrialise. By 1900, US industrial output matches that of Britain, France and Germany combined.

The Europeans can see a continental power emerging that, unlike them, contains within itself huge quantities of the natural resources necessary for a modern industrial economy. The Monroe Doctrine, first proclaimed in 1832, starts to bite in the Americas. Even on the other side of the Atlantic, the Europeans begin to fear American domination.

The fear is turbocharged by the rise of oil as the preferred source of power for transportation. While Europe has coal, it has no oil – but America, it gradually turns out, has oceans of it.

The fear of American power lies behind the scramble for Africa in which the Europeans seek to secure the natural resources that the US already has. It lies behind European interest in the Middle East. Later on, it lies behind Hitler’s push for Lebensraum. It also prompts early articulations of the pan-European ideal that eventually finds expression in the European Union.

As things turn out, it is rivalry between European powers that catastrophically dominates the first half of the Twentieth Century. Coming out of the Second World War, the European powers are broken. However, the United States faces a new threat in the continental and ideological power of the Soviet Union.

Charles de Gaulle is preparing to govern Europe in alliance with Britain, an arrangement in which Germany is to be denied the industrial capability that might permit it to launch a third war. However, the Americans conclude that German industry is needed for western Europe to resist Soviet domination. De Gaulle breaks with Britain and forges the European Coal and Steel Community, the forerunner of the EU, in order to retain some degree of control over German industrialisation. Nato follows and the pattern is set. The goal is to keep the Soviets out, the Germans down and the Americans in.

This arrangement is buttressed by an ideological unity forged by Roosevelt and Churchill. The Free World, or simply The West, is capitalist rather than communist (but with scope for a welfare state), free rather than controlled, governed by laws rather than a party.

The defeat of communism and the peaceful reunification of Germany in 1990 begets a naïve optimism. There are 30 years of strategic confusion on both sides of the Atlantic in which the allies fundamentally disagree about i) how they should relate to Russia, the former members of the Warsaw Pact and Turkey; and ii) the roles of Nato and the EU. Under general economic pressure, the Europeans run down their armed forces

Today, the Europeans remain incapable of defending themselves even against a Russia that is a pale shadow of the Soviet Union. Germany has the economic and fiscal strength to fulfil the central role the US originally saw for it but, thanks to the constitutional constraint it put on debt in 2009, declines to do so.

The US, at least the Trump version of it, is abandoning the shared ideology even as China poses a new threat. Relishing America’s power, it is returning to earlier ambitions and wants the Europeans out of the Western hemisphere, hence Trump’s Canada and Greenland gambits. For now, the re-articulated territorial ambitions, disturbing as they are, may seem more like cosplay than the real thing, but in the future – who knows?

Against this tumultuous backdrop, it is easy to see how the oligarchs standing in the front row at Trump’s inauguration get what they want. It’s that or risk an early, adrenaline-fuelled showdown with our most important ally, a battle that could derail Keir Starmer’s entire project.

Vassal state

Thompson, a professor of political economy at Cambridge, considers American power as an external force. By contrast, Angus Hanton, a businessman turned author, looks on it as a force that has come to be deeply embedded in our economy. In Vassal State, he traces this dependency back to Margaret Thatcher.

In the 1980s, Thatcher encouraged the sale of British companies, partly by renouncing and then removing legal powers that allowed the government to prevent foreign takeovers of British firms. She also initiated the privatisation of many public sector activities. These moves, perpetuated under New Labour, resulted in a flood of US takeovers of both British companies and public sector operations. The US now controls leading companies across huge swathes of the UK economy, from real estate to food, from bookstores to pharmacies. The UK now accounts for half of all US assets in Europe and US firms employ some 2 million workers, more than in France, Germany, Italy and Spain combined.

The number of firms trading on the London Stock Exchange has fallen by 40 per cent since 2008. Firms have been taken over, taken private by US private equity firms or relisted in New York. In 1981, less than 4 per cent of UK shares were owned overseas; today it is more than 56 per cent.

The shift to online services has accelerated this dependency. Amazon, PayPal, Visa, Ebay, Uber, Deliveroo, Netflix – the list of American firms skimming percentages out of the British economy goes on and on. While the UK’s economic performance has stagnated since 2008, the UK profits of US tech firms have rocketed. And aggressive tax avoidance strategies mean these companies hardly pay any tax on their profits here.

The consequence is impoverishment, loss of autonomy and a drain on talent and treasure. This decline has been obscured by what Hanton calls the big lie – the systematic conflation of money spent buying shares in takeovers with genuinely useful foreign direct investment in, for example, a new factory.

On this account, faced with pressure from Big Tech, the British government folds because it’s already the case that, as the book’s tagline puts it, “America runs Britain”. The UK is already so hollowed out as a power, so subservient economically to the US that the idea that it should attempt to stand against America’s biggest and most powerful corporations is naïve.

Good job

Published last spring, Vassal State considers the eventuality that has now come to pass, of the US under Trump abandoning the ideology it has long shared with the UK, and concludes we risk ending up in the same kind of relationship with the US that Belarus has with Russia. It is therefore a book that is both prescient and alarming. It is, however, not nearly alarming enough.

As Tom Hazeldine points out in the blog of the New Left Review, Hanton neglects the longstanding exertion of US power via monetary policy:

“… foisting sterling convertibility on Attlee in 1946 after Truman abruptly terminated Lend Lease (a ‘financial Dunkirk’, according to Keynes), forcing Eden into an immediate troop withdrawal from Suez in 1956 in return for emergency funding to maintain sterling parity, blocking devaluation by Wilson in 1965 and leading Callaghan into IMF austerity in 1976. The institutional nexus of US financial influence continued into the twenty-first century with the dollar swap lines of 2008 and 2020–21”.

Today, the key point is the last. The dollar swap lines were lines of credit provided to banks in the UK from the US. So far as I know, and unlike the earlier items in the list, their deployment lacked a coercive element and merely kept British banks from going bust. But the upshot is that the lender of last resort to the British financial system is now not the Bank of England but the Federal Reserve.

Hanton describes how big US firms have penetrated the very top of British politics. Those who have taken the corporate dollar include Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron, George Osborne, Nick Clegg and Rishi Sunak. These leaders, he says, ‘have been coopted into the American machinery of influence and have rarely, if ever, questioned its growing dominance’. However, he was writing before the US election brought the tech oligarchs who dominate the media in both the US and UK into the front row of the president’s inauguration. The main reason he refers to Musk is to note his claim to sleep in the Tesla factory and hence to illustrate a supreme work ethic. He therefore underplays American influence over British media and politics and the extent to which it undermines what he identifies as our key remaining strength – our democracy.

Part of this influence is exercised via the social media platforms owned by Musk and one of his neighbours at Trump’s inauguration, Mark Zuckerberg. Part of it is exercised by the money flowing from Silicon Valley to UK political entrepreneurs including Nigel Farage, Tommy Robinson and Blair. In practical terms, the most important of these right now is Blair because his faction includes Kyle and Streeting, secretaries of state with the power to resist or assist. His support from Oracle’s Larry Ellison is now rising towards $400 million.

Thus we have a third way of understanding American power. Starmer’s government gives Big Tech what it wants because it is under direct political pressure from Silicon Valley, both from within (Cabinet ministers) and without (social media). It is noticeable that as the Big Tech-friendly policy decisions have come through, so the lurid attacks by Musk on X that led, for example, to death threats against Jess Phillips, have faded. On 26 January, Trump told the BBC that Starmer had done a "very good job thus far".

The shiver

The events of the last two weeks in the US put into a new and darker light the approach to government articulated by Blair and William Hague in A New National Purpose two years ago. This project has matured into one involving more than 70 reports and Cabinet ministers including both Kyle and Streeting. It argues for a transformation of the state in terms that are vague but which include a smaller state with power centralised in 10 Downing Street and ministers recruited from business rather than Parliament. Technology, especially AI, is to be used to transform government and public services. Although I have been skeptical of this project, at no point did it cross my mind that it might pave the way to a Britain that is oligarchic and authoritarian. Now, looking at what is unfolding in the United States, a shiver of recognition runs through me. It’s as if I’ve already read the playbook.

Trump also promised a different kind of state in terms that were vague but included making it smaller and concentrating power at the centre. Now we see that the vagueness can be used to legitimise the oligarchising of politics through the determined undermining of alternative sources of authority in the civil service, legislature and legal system – steps that do indeed make the state smaller and concentrate power at the centre. This, one could say, is the very definition of Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) – it cuts spending (makes government smaller) by taking control (concentrating power).

At the same time, just as Blair and Hague proposed for the UK, technology has emerged in Washington as the spearhead through which transformation of the state is effected. Musk has appointed technologists to seize control of systems used by a wide variety of government departments. This includes most consequentially the system used by the US Treasury to disburse payments across government. There is in practice nothing, it seems, to prevent these technologists from copying all the data in government silos, including that on individuals and companies, nothing to stop them pushing to live undocumented alterations to source code.

This makes clear why technologists on the other side of the fence in the US have long been warning individuals to sanitise their digital doppelgangers, the versions of us recorded in online systems and which shadow our real lives. You may be law-abiding, they have warned, but if you are the wrong kind of person, live the wrong kind of life or say the wrong kind of thing then, under Trump, the state may come for you. Or it may pass your details to non-state actors who will come for you.

In Washington, the United States Digital Service has been re-fashioned as DOGE, the vehicle for Musk to seize control of operations across the whole of government. In London, Kyle has re-fashioned the Government Digital Service as the new ‘digital centre of government’ with a cross-departmental remit. The role of Kyle’s unit is couched in terms of improving public services, but it can be seen as the embryonic form of something Blair and Hague have already called for: “a central strategic and delivery unit, optimised for science and technology, to act as a centre of political and state power” – the British equivalent of Musk’s DOGE.

Just as Project 2025 provided the detailed basis for rapid action once Trump took office, so the 70+ reports flowing from A New National Purpose have provided the detailed basis for the rapid promotion of technology across government by Kyle and Streeting. In Britain the effect has been far more limited, but then the Blairites are only the junior members of the governing Labour coalition and in no position currently to fashion a Brit-DOGE.

This isn’t to suggest the Blairites, and their allies in the Haguite ranks of the Conservative Party, are about to start delivering Nazi salutes. Thatcherism 3.0, as I have called this alliance, aren’t fascists. However, Blair is a (techno-) populist and this means there are continuities between him and Musk. For example, they both posit independent bastions of authority, such as the civil service, as opponents of the people that must be defeated. So, given what is happening in Washington, it no longer seems incredible to fear that what starts with Blair could end with another populist, such as Robinson.

This fear is accentuated by the most obvious difference between Musk and Thatcherism 3.0, the ultimate political end that has been articulated. Even though he has fallen out with some of them, Musk’s overt political goals are drawn from the MAGA crowd. That salute hints at some of them and, disturbing as they are, they are tangible. By contrast, Blair and Hague have left a vacuum at the centre of their project. They have said that technology itself should be Britain’s new national purpose, an ambition so empty that it leaves ample space for something else to take its place in future, perhaps darker, perhaps oligarchic.

Or perhaps American. It is already the case that Microsoft servers are the preferred choice for many of the public sector’s digital operations. Compared to Google, Microsoft offers better data sovereignty and, given the ordinary legal regime, this reliance inspires no dread in me. But if Farage is installed in 10 Downing Street with the help, and debt, of Musk money and X propaganda, he can follow the Musk playbook and bring with him a platoon of technologists to ‘transform’ the state. Blair and Hague have already taught us to treat such proposals as quite normal. At which point effective control of the machinery of the state could pass from the UK to the US in a matter of days.

This is the kind of technological singularity we need to be worried about.

PS. A reminder that the first, open meeting of the new Kings Cross AI and Democracy Group will take place this coming Wednesday. You can sign up here.

Very helpful post. I’ve been trying to get my head around what ministers are trying to do here. Reynolds comes closest when he says he wants regulators to be pro business in order to drive growth. As you observe that might well not be the same as promoting the UK’s strategic economic interests, helping consumers and certainly isn’t the remit of the CMA which is to prevent abuse of market power. I also see a report in today’s FT that ministers aren’t keen on private operators competing with the nationalised train franchises. All a bit of a mess but ultimately looks like there’s a strong anti competition streak in the present administration.

The Kill Zone is real