“Britain has become a byword for ineffective industrial policy.”

This is a line from an upcoming book on industrial policy in the US currently being reviewed by the economist Diane Coyle, so I can’t tell you who wrote it. But we don’t need to know. This is a line that has poetic force. It tells us something that, deep down, we already know.

Since Margaret Thatcher decreed that the government should get out of near-market research, industrial policy has consisted largely of support for the research councils, later expanded with Innovate UK, R&D tax credits and SME support via the British Business Bank. Regulatory control over, for example, takeovers of strategically important companies has been abandoned. The idea of the state investing in industry, or even partnering with it as via the National Economic Development Council, has evaporated. With Brexit, the idea of some element of strategic investment beyond infrastructure via mechanisms such as the European Investment Bank also evaporated. As David Edgerton asks, what has this new approach achieved? Where are the great British companies that it has nurtured? Where are the jobs?

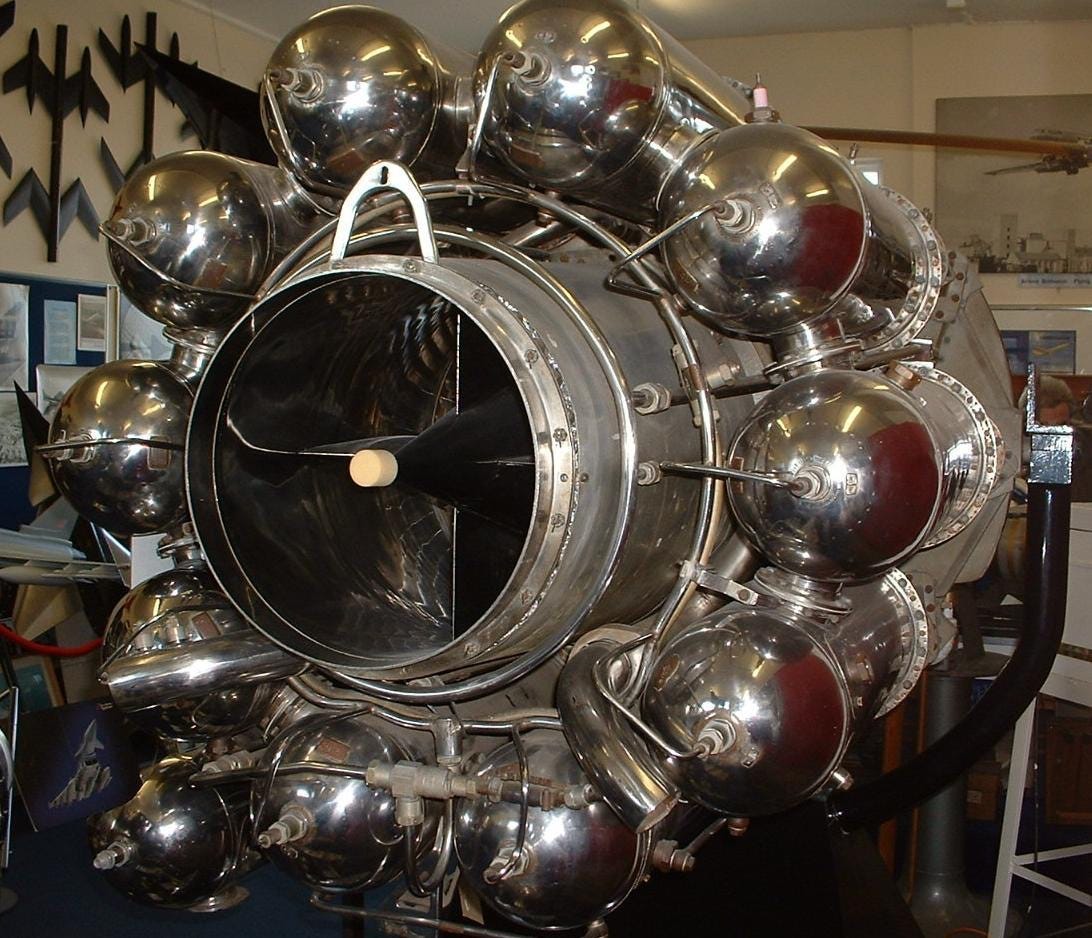

The failure is thrown into stark relief when we consider the one area in which the UK has consistently pursued an old-fashioned industrial policy throughout this period, aircraft. In aircraft, the UK has continued to provide the industry with large, soft loans for the development of new products, and it has continued to use its political leverage to the benefit of the industry in the UK. As a result, when so much of our industrial capacity, from manufacturing to chemicals, has disappeared, we still have a high-tech aircraft industry in the UK providing thousands of great jobs in areas outside the Golden Triangle.

So we have to be extraordinarily careful in pursuing the idea of a cross-party consensus on science and by extension industrial policy. If that consensus is the same one that has governed policy in the UK for the past 40 years, it is a consensus of failure.

Today there are three currents that are steering Labour towards a new kind of industrial policy.

The first is that growth and productivity are stagnant. Labour has to get the economy growing again, and make sure the fruits of that growth are shared around. Contrary to Thatcher’s laissez-faire instincts, a growing body of economic evidence now supports an active if nuanced role for the state in addressing this problem.

The second is strategic. It stems from China’s break with the kind of globalised economy that was imagined in the 2000s and 2010s. It is now pouring huge subsidies into selected industries with the aim of capturing global markets. It has picked its winners. This has prompted the US to respond in kind. Even the EU, hamstrung by its own internal market rules, is moving in the same direction. If Britain does not become more self-sufficient in strategic industries from chemicals to chips, it risks being economically, militarily and politically dominated. Hence the spooks now floating around the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.

These two currents can be seen as embodying Rachel Reeves’ idea of securonomics, addressing on the one hand the insecurity of the individual in a weak economy, on the other the insecurity of the nation in a world where the old rules no longer apply.

The third current is political. The costs of the net zero transition have been sold to voters in part on the promise that the transition will give birth to a wave of new industries, and the jobs that come with them.

These three currents both intermingle and pull away from each other. It’s possible to imagine policies that serve them all, for example one aimed at turning Britain into a centre of battery manufacturing. However, it’s simpler at first to look at them separately, and in reverse order.

With regulatory support, there is useful stuff that GB Energy can do. For example, Labour’s new institution can get more wind turbines into service, both offshore and onshore. However, this is not going to create much in the way of new manufacturing because the turbine industry is already locked up in other countries. Those offshore turbines will be bought primarily from either China or Denmark, and the same is true of other leading transition technologies. Solar? China. Batteries? China. Electric cars? China. With the Inflation Reduction Act and trillions of investment, even the US is now playing catch up, but with no clarity about whether it will succeed.

Where GB Energy could serve industrial policy effectively is by bringing down the price of electricity below that of competitors in Europe. But that is a very distant hope. However much Labour’s electoral coalition wants to believe net zero will be win-win in the UK, there is still no path in sight to that promised land.

Turning to the strategic argument, during the election campaign I heard the Conservative former science minister David Willetts speak at a hustings at the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences. He contrasted the British experience after Suez with the French one. In the days following the debacle, and looking at France’s now tenuous energy security, President Pompidou commissioned a fleet of nuclear reactors and a high-speed rail network. In Britain, despite fuel shortages that left factories idle and cars in the garage, no decisive action was taken and instead we got the white elephant of Concorde. Willetts’ conclusion was that if you’ve had the French experience, you can be confident of making industrial policy work; if you’ve had the British experience, you can’t.

This view shares Thatcher’s aversion to picking winners, but on the grounds of political culture rather than economic principle. It is a new twist on the old consensus of failure that makes it applicable even in the strategic context. Unfortunately, it has even less evidence in its favour than the old version. An alternative response to this history is that the thing that should be repudiated is not industrial policy but the political culture that made Britain so bad at it; perhaps Harold Wilson was right all along.

This leaves the issue that is central economically and, because of the rhetorical importance Labour has attached to it, politically – growth. Can this be achieved without some kind of industrial policy? Does that policy have to rely on picking winners? Can it be done in a way that shares the fruits of growth around? Which comes first, skills or capital? And does the UK have the money to do anything anyway? Come back next time for answers to all these questions…