Concorde, HS2 and the dangerously seductive idea of a cross-party consensus on science

Techno-nationalism never went away, it just degenerated

Before Christmas, Greg Clark was appointed to the new Industrial Strategy Advisory Council. Clark was the director of policy at Conservative Central Office for Michael Howard and Iain Duncan-Smith and the Business Secretary under Theresa May. Alongside figures such as David Willetts, William Hague and George Osborne, he is one of the intellectual generation of Conservatives that brought the crazy into the party and now find themselves being consumed by the revolution. Clark’s appointment means the only MP on the ISAC is a Conservative. And the only reason for a Labour government to make such an arrangement is to build a cross-party consensus in this area of policy, an idea I wrote about repeatedly last year.

The primary hope for any consensus is stability of policy. The instability that we have had over the past 14 years of Conservative government has made companies more reluctant to make large investments, such as in new factories, and exacerbated the UK’s chronic short-termism. But this then raises the question of what Clark and his allies have to offer other than warm words.

Smoke and mirrors

The instability has arisen from a two and a half-sided game of ping pong in the Conservative Party that reflects factional ideological differences that are routinely obfuscated with insincere language and tactical silence. On taking office in 2010, Willetts had a change of heart over scrapping the Technology Strategy Board (now Innovate UK). In a series of speeches, he set out the case for repudiating the dogmatically laissez faire approach implemented under Margaret Thatcher by Peter Lilley. These speeches crystallised an ideological difference in industrial strategy between two enduring tendencies I have labelled Thatcherism Mark I (Lilley and co) and Mark II (Willets and co).

Willetts’ signature policy then was to focus significant funding on a list of ‘eight great technologies’. This established the distinctive linguistic tic of Thatcherism Mark II – talking of ‘industrial strategy’ while pursuing a purely technological approach that eschews investment in ideas that have moved out of the lab and into the market.

As reflected in the decision not to scrap the Technology Strategy Board, Willetts’ approach overlaps heavily with that of New Labour. This continuity is reflected in many other areas of policy and means, I think, that the simplest way to understand our recent history is that Thatcherism Mark II has Conservative and Labour wings and remained the dominant power in all governments from 1992 through until 2019.

In 2010, Thatcherism Mark I found itself out of office. There was no public dispute with Willetts, but this silence did not signify acquiescence. It was merely biding its time. In 2015, when the Conservatives won a majority of seats in the House of Commons, David Cameron made Sajid Javid the Business Secretary – and he set about dismantling the measures Willetts had introduced. ‘Industrial strategy’ disappeared from the government’s lexicon.

Mark II returned to office when Theresa May made Clark Business Secretary. A new technology strategy was published with the words “industrial strategy” on the cover.

Boris Johnson appointed Kwasi Kwarteng, who scrapped May’s Industrial Strategy Council, and the term “industrial strategy” was again banished. Johnson I think is a mixture of old and new, and this is why I say the ping pong has 2.5 players. On the one hand, there is a continuity with Thatcherism Mark I, reflected in the repudiation of the concept of industrial strategy and the reliance instead on the boosterism of Britain as a “science superpower” – language that makes limiting government support to academic, far-from-market research entirely natural. On the other hand, there is a break, as evidenced in his cavalier approach to constitutional and epistemic norms, a flirting with the dark side of techno-populism that he shares with Nigel Farage.

Rishi Sunak pursued a hybrid of Mark I and Mark II. On the one hand, he avoided the term “industrial strategy”. On the other, at the behest of the Mark II alliance as it mutated into Thatcherism 3.0, he created the Department of Science, Innovation and Technology, a unit that creates an institutional break with near-market research and which, under Labour, can adopt the term “industrial strategy” without deviating from the pre-existing course. Today, the Johnsonian mix of old and new can be found in the way Lilley and David Frost, an architect of Britain’s hard Brexit, have come together as climate change skeptics with revolutionary zeal to accuse Willetts and his colleagues of being socialists.

The question is, how is Clark intending to stop the ping pong happening again if the Conservatives get back into Number 10? And the answer is, he can’t, especially in the tumult that has now engulfed the party as Reform’s support grows. Thus the idea of a cross-party consensus is one that promises something it is not capable of delivering and cannot be taken at face value. Rather, it has two functions. First, it is an implicit excuse for failure; it says that Thatcherism Mark II’s approach would have worked if only Thatcherism Mark I hadn’t got in the way. Second, it creates a kind of political potential.

There are three different ways the potential can be fulfilled. The first lacks consequence and makes the consensus a best efforts move by the Labour government to reassure potential investors. If Clark and allies disagree with some of Labour’s policies, so be it.

A second way for the consensus to emerge is as one that supports an activist industrial strategy that extends into the market, as flagged in the new government by Ed Miliband’s development of Great British Energy. Given that this involves repudiating the no near-market shibboleth that has been a consistent feature of all strands of Conservative thinking for 40 years, that hardly seems likely.

Thatcherism 3.0

This leaves the third way that a consensus could emerge, as a consensus over science. This is how I first came across the idea, as it was articulated by Willetts before the election and taken up by The Royal Society. The government would continue to place heavy emphasis on supporting academic research while steering clear of supporting near-market activity.

Such a consensus would be consistent with A New National Purpose, the techno-zealous manifesto published by Tony Blair and William Hague two years ago. It thus is capable of embracing the Blairite faction in Labour and advancing the project I have called Thatcherism 3.0. This strengthens the hand of Thatcherism Mark II within both the Labour and the Conservative parties through a shared manifesto, closer coordination, the creation and control of DSIT, and an alliance with Big Tech.

To maintain unity within the Labour Party, Keir Starmer has ceded DSIT to the Blairites, but it’s not a blank cheque. Ultimately, the department’s policies must serve the larger goals of the government. And it is noticeable that despite the appointment of Clark to the ISC, the phrase “cross-party consensus” on industrial strategy has not passed the lips of any Labour minister in public.

Thatcherism 3.0 is not the ‘uniparty’ that Farage has cribbed from Steve Bannon and was pushing with Laura Kuenssberg on Sunday. Both concepts rely on the widespread observation of deep continuities across changes in governing party in the UK. However, the idea of a uniparty wilfully ignores differences within the parties. On the Labour side, it disappears the sincere social democrats who were never signed up to the New Labour project. On the Conservative side, it glosses over two inconvenient facts. First, that the Conservatives have repeatedly implemented Farage’s policies, including both the in/out Brexit referendum and the subsequent hard Brexit. Second, that Johnson’s government was in many respects a Faragiste administration. The Britain we have today has been shaped as much by Farage as anyone.

The alliance with Big Tech has been cemented by the $100 million given to the Tony Blair Institute by Larry Ellison, the Oracle founder. The extent to which Thatcherism 3.0 shares ideological DNA with the sometimes alarming stuff coming out of Silicon Valley should become clearer next month with the publication of a book that aims to turn tech into the national purpose of the USA, The Technological Revolution by Alex Karp. Karp is the chief executive of Palantir and, like Elon Musk, one of Peter Thiel’s protégés.

The idea of a consensus on science encapsulates the pre-eminent industrial doctrine of the past 33 years, the Thatcherism Mark II that governed policy from 1992 to 2015, from 2016 to 2019, and from the creation of DSIT in 2023 onwards. This dominance over so many years undermines any excuse for the economic failure. And it prompts an obvious objection to this kind of consensus, that it will have the same result as before – industrial decline and poverty in half the country.

There is, however, a second objection that is the opposite of obvious.

Techno-nationalism

After the Second World War, Britain had a consensus on industrial strategy. This period, important in our political imagination, has been examined recently by the historian Tom Kelsey. In The Retreat from ‘High Technology’ in Post-War Britain he charts a change of attitude in the 1970s when the British state withdrew from ‘picking winners’.

During the 1970s, a once powerful future in which British technology was central came to an end. Dreams of a nation supplying itself and the world with the products of inventive genius had turned into nightmarishly expensive programmes. The optimism of state engineers and private industry, once so enthusiastically encouraged, was no longer taken seriously and, indeed, was seen as dangerous. In the eyes of administrators and many ministers, three decades of techno-nationalism had not secured industrial dominance for the nation but weakened it.

The costs of programmes to build supersonic aircraft and nuclear reactors were huge. At one point, there were 20,000 people in the UK alone working on Concorde.

…by the late 1960s and early 1970s, Whitehall itself, and the Treasury in particular, offered a standard liberal line of argument: they wanted state-sponsored Research and Development spending to be driven by industry, not the state. Because of this, Britain went from having a remarkable faith in state engineers to a deep wariness. In addition, this reduction in the faith of the state was not a mere abstract ideological move, but partly the result of spending decades building aeroplanes and nuclear reactors no foreign country wanted to buy.

There are a wide range of reasons over decades why governments of both hues persisted with these two huge programmes including: to compete with the Americans for global leadership in technology and prestige; to earn foreign exchange; to keep faith with the engineers; to remain a reliable partner for international collaborations (rather than quit Concorde unilaterally); to avoid wasting sunk costs; to keep important companies in business. Underpinning all these concerns was a British techno-nationalism, an idea that for Kelsey “is centrally concerned with geopolitical struggle as well as status—it is about which nations will build the global future”. For decades, this techno-nationalism defeated, as much with subterfuge and delusion as argument, those who wanted to coolly assess the economic case for the programmes as early optimism evaporated.

Now, an aversion to picking winners is a cardinal principle of the Thatcherite consensus of the past 40 years. It therefore should have been impossible for all the errors and costs associated with Concorde and nuclear reactors to be repeated by New Labour or the Cameron-Osborne government. But it has been repeated. And it was the result of exactly the cross-party alliance of factions that now wants to construct a consensus on science. It is called HS2.

Rather than engineers, the initial driving force behind the HS2 project was railway planners. But just as the engineers saw a plausible economic rationale, so did the planners. Britons were losing a huge amount of working time on train journeys. Faster journeys would increase output; the savings could be quantified and were larger than the estimated costs of the new railway. But as before, the economic case didn’t stand up.

The company to develop HS2 was formed by Cameron in 2009. This is the iPhone 3GS, the model of 2009:

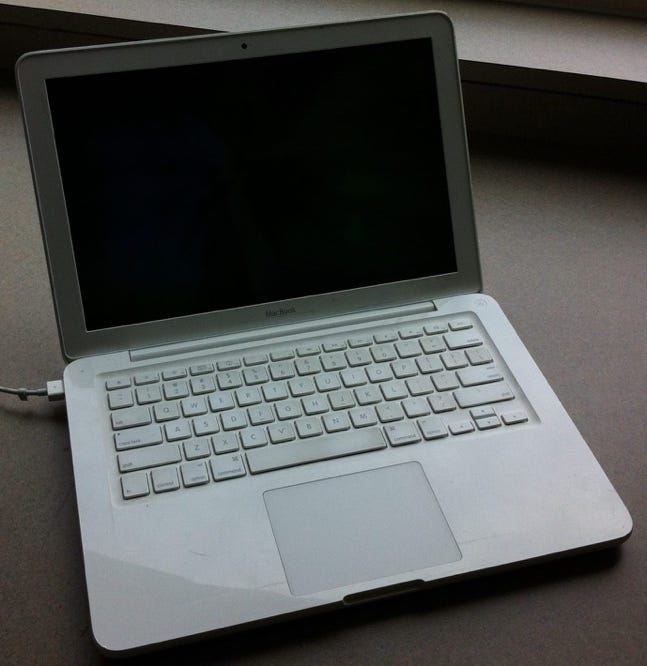

This is the MacBook of 2009:

The 4G iPhone landed the next year. The days when people could work on the train had already arrived and the cost case for high-speed rail was junk from the outset, just as the then flag carrier BOAC said from early on that Concorde would be too expensive to run.

Not junk was the need to increase rail capacity. However, at no time during the entire history of HS2 was any evaluation published of a new line that ran at any speed less than 360 km/h. The cost savings would have been huge. A non-high-speed line can have tighter turns, which means fewer tunnels and bridges. It can use cheaper construction methods and materials. There is less sound pollution, so there is less need for sound barriers. You can use more basic signalling systems. You need can use cheaper rolling stock that is simpler to maintain and uses less power.

In addition, a line where speed was not the critical issue could have gone around instead of through the Chilterns, again removing a need for tunnelling. A different route and lower speeds would also have diminished the temptation for the Conservatives to do the thing that piled up costs in the south and killed off the northern legs of the project – featherbedding constituencies with Conservative MPs by building sound-insulating tunnels even when the line is running on the flat.

Those now lobbying for a non-high speed extension to the current HS2 plan in the north are claiming their plan could be 40 per cent cheaper. Thus it seems to me quite reasonable to think that the new line could have been built for half the price, and that what we’ve already spent on the line would already have built the additional northern legs.

How did this fiasco happen? One thing that can be said for the politicians picking winners in the 1950s and 1960s was that they were engaged primarily in the task of governing. But since then, the character of politics across the West has changed. The connective tissue that linked voters with politicians – party structures, trade unions, churches etc – has evaporated. Politics has acquired a lightness in which the politicians float, disconnected from any distinct part of society such as the working class. As in other countries, the politicians of the Thatcherite consensus responded to this by concerning themselves primarily not with governing but with what previously was considered the froth of politics, inhabiting and seeking to shape a bubble of media and social media storms.

In this context, techno-nationalism is obliged to take on a new character. It ceases to be about the substance of geopolitical leadership and starts to be about winning elections. The value of technology lies not in what can be achieved but in the impression that can be created. It becomes degenerate.

For degenerate techno-nationalism, HS2 had everything that was required. Like Concorde, it came with the glamour of new technology and the thrill of speed. It promised that the politicians creating it knew how to grasp the future, inspiring both confidence and optimism. It symbolised a high-tech economy even as the UK’s position in high-tech industries continued to crumble. Exemplifying this shallowness, Peter Mandelson, who included HS2 in New Labour’s 2010 general election manifesto, has said he only backed the idea in order to upstage the Conservatives.

The fiasco of HS2 occurred because the new, degenerate kind of techno-nationalism bulldozed all objections from those who wanted a cool assessment of the economic case for the project, just like the old kind did 50 years before. The detail of how this played out – how rail planners got the bandwagon going, how the cool head of Alistair Darling was circumvented, how critical flaws in the economic case were identified in advance but still ignored – can be read here.

Degenerate techno-nationalism has been embraced by the promoters of a cross-party consensus on science, Thatcherism 3.0. It can be found in Blair and Hague’s A New National Purpose where it is elevated to the purpose of the state itself. It can also be found in the subsequent wave of more than 70 reports from the Tony Blair Institute that promote technology as the solution to a range of the country’s ills. Over and over, these reports give technology a decisive role while skirting enveloping questions of down-to-earth practicality. They are degenerate techno-nationalism in the form of a swarm. If you are buying all this, then one of the things you are buying is more débâcles in the tradition of Concorde, nuclear reactors and HS2. This is the second, non-obvious objection to the idea of a cross-party consensus focussed on science.

Substance

Excluded from a consensus on science is social democracy, the neo-Bevinism of soft left figures such as Alastair Darling, Frank Dobson, Ed Miliband and, at heart, Starmer. The routine accusation that such figures are dull and unglamorous is just the flip side of the coin of substance.

Starmer’s prioritisation of “working people” is not just rhetoric. His first King’s Speech is full of legislation to strengthen the position of workers. And this reflects a commitment to represent the interests of a certain part of society, albeit a part that in a far more fluid society cannot be defined as neatly as the working class was in the 1940s. It should be contrasted with New Labour’s rhetoric of “the people”.

At the same time, Starmer is prioritising the art of governing over the art of politics. This is exactly how it became possible for commentators who cannot see beyond the bubble to obsess about a supposed lack of narrative.

The substance in social democracy is the nation’s protection against repeats of the disasters of Concorde, nuclear reactors and HS2. Dobson shows the way. Build more homes. Increase spending on the NHS. Improve the way it works with effective innovations such as the National Institute for Clinical Excellence and NHS Direct. Disdain glamour. Make technology and technology companies the servant, not the master. Because the government must, must, must deliver for working people, it cannot afford the luxury of grand projects where the economics don’t add up.

This doesn’t mean not intervening in the market. It means making cool assessments of the case for intervention and using the country’s resources to develop systematic approaches that are effective at scale. This is how I, a social democrat, come to advocate for the government to invest in the economy through the mechanism of venture capital. I expect such an approach to be effective in eroding some of our deepest economic problems, creating good jobs in the parts of the country that need them most. At the same time, by investing in a wide portfolio of companies, co-investing with private investors on the same terms, and by leaving the choice of investments to cool heads in the venture capital firms, I am ensuring there will be no repeat of the disasters of Concorde, nuclear reactors and HS2.

In short, there is no reason for Britain to fear an approach to industrial strategy that breaks with the neoliberal, Thatcherite no near-market consensus that has shaped the country for the past 40 years. Indeed, the bigger risk for Starmer is hobbling his own options by choosing to let himself be constrained by the siren voices of those that want a cross-party consensus on science.

William, I very much enjoy your analysis of industrial strategy. Thank you.

Good analysis but in the end, are we just talking about the tendency of elites of all political shades to obsess over very large machines? I don't see how venture capital is a solution, non-existent track record on investing in technology that responds to societal needs. My vote - it would be better if we had S&T policies that involved citizens more deeply in policy design and gained their active consent. In the 1990s and early 2000s such policies were actually proposed at the EU level but nothing happened.